Mentorship, Respect and Belonging: What Boys Are Really Asking For

Okay, I am a parent of three boys — aged 15, 17 and 19.

So, I recognise my bias when I position myself as this article’s creator.

The thing is… I was not expecting to be a mum of boys.

I worked at an all-girls camp in Ontario during my summer holidays.

My early career was spent teaching in all-girls’ schools.

I even had a name picked out for my daughter — Olive Low, after her great-grandmother.

And, I’m slightly embarrassed to admit, at one point I knitted a cream-and-pink scarf in hopeful anticipation of her arrival.

So yes — it came as quite a surprise to learn I was expecting a boy…

not once, but three times.

Two hands holding knitting needles knitting a scarf

All this to say: I am utterly blessed with my sons, and I wouldn’t change it for the world. They’ve expanded my understanding of adolescence, learning and connection in ways no degree ever could.

And yet, while I do my very best in professional spaces to avoid gender stereotyping, with my own boys?

Let’s just say the evidence sometimes stacks up against me.

How many times can one parent remind their child that a wet towel will not dry when crumpled on the floor?

I am regularly rugby-tackled in the kitchen.

Dinner conversations often revolve around rugby scores, football stats, & F1 pole positions.

(Not to say that only boys do this and/or not all boys do. It may simply be my boys.)

But here is something I feel deeply:

adolescents, and boys in particular, are often profoundly misunderstood.

One of my sons especially has been misread for much of his childhood and adolescence.

And after 18 sanctions by October half term… it gets tiring for us, him and I am sure his teachers. When we were discussing this, he said, ‘don’t worry mum, that boy has 42 sanctions!’

I wonder if we looked at behaviour through a different lens, rather than through compliance, to what the behaviour is really communicating. This has become the very heart of my work with schools and families: looking beyond the behaviour to understand what is happening for the young person, rather than what is wrong with them.

Instead of…

“He’s being disrespectful”…to “He’s seeking respect and status.”

“He’s constantly testing me”…to “He’s seeking connection'.”

“He just flips when something feels unfair”…to “His body/brain feels unsafe and threatened.”

So when I came across David Yeager’s research — in combination with the neuroscience coaching I’ve immersed myself in over the last two years — it blew my mind.

I even tried to share some of the research with my sons (including the David Yeager’s “nagging study” which is a MUST read…essentially nagging DOES NOT WORK!)

All I got back was tumbleweed…

and variations of:

“Please Mum, no more psychology.”

Fair enough.

But here’s the part they don’t yet know:

What I’ve learned about status, fairness, safety and belonging has transformed not only how I understand teenage boys — but how I teach others to understand them too.

For many adolescent boys, behaviour is not about rebellion.

It’s about biology.

During adolescence, the brain rewires itself at an astonishing pace. Systems linked to status, fairness, identity and belonging become hypersensitive. The areas of the brain that assess social cues - the medial prefrontal cortex and the ventral striatum - light up dramatically when boys feel respected… or when they don’t.

What often looks like defiance is actually a nervous system saying:

“Am I safe? Do I matter? Do I belong?”

Status Isn’t Superiority — It’s Safety

David Yeager’s work on adolescence and motivation shows that young people interpret status not as dominance, but as social safety. When they feel respected, believed in, and treated fairly, their brains stay open to learning. When they perceive humiliation or injustice, the brain switches into defensive mode.

The amygdala fires.

The prefrontal cortex goes offline.

The nervous system prepares for fight, flight or shutdown.

This is not attitude.

It’s neurobiology.

The Trapdoor of the Habenula

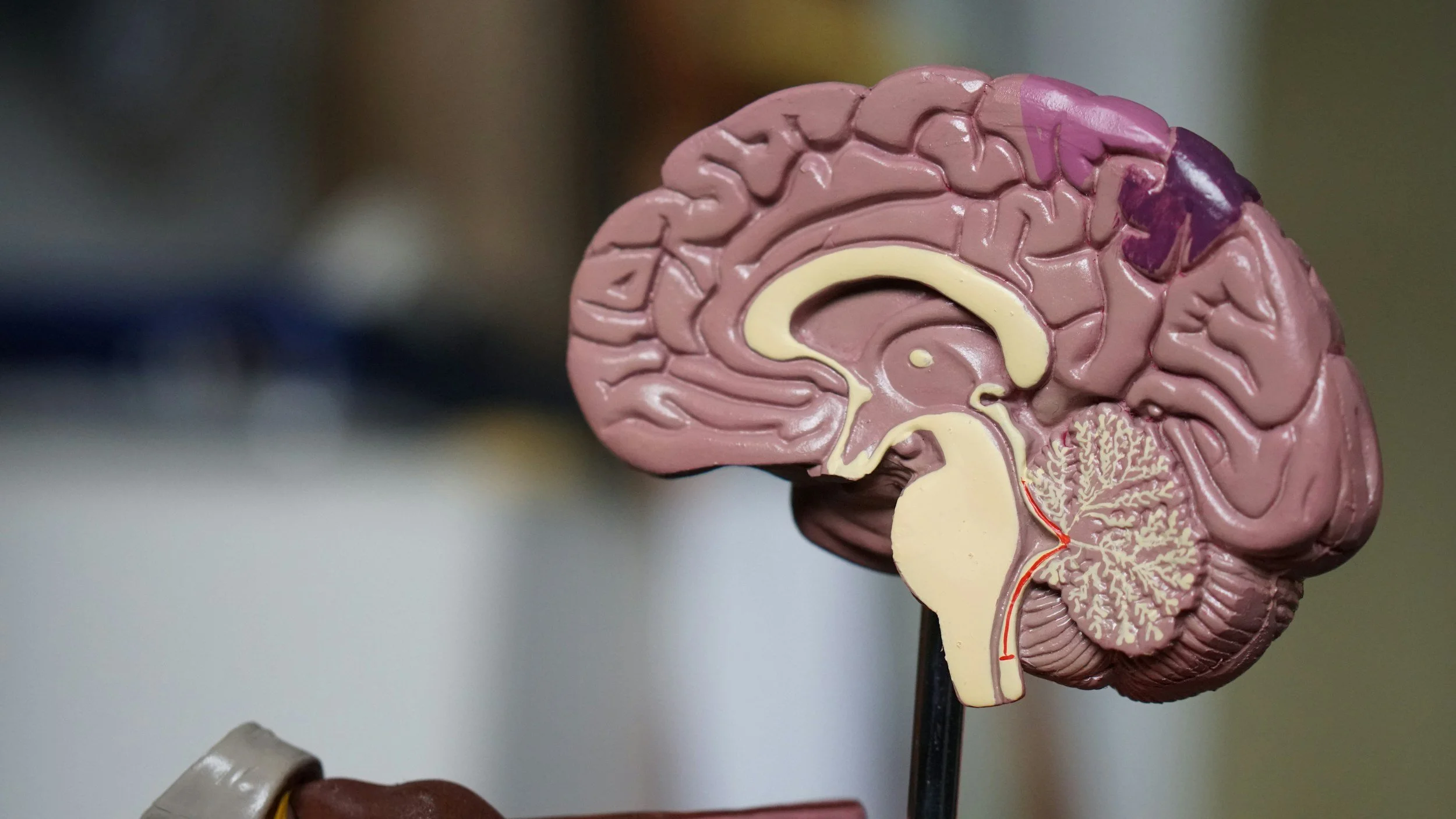

A model of a brain: The habenula is a pair of small nuclei located above the thalamus at its posterior end close to the midline

The habenula - a tiny structure deep in the brain - reacts to failure and social pain. When a boy feels publicly shamed or dismissed, this “tripwire” suppresses dopamine and motivation. You’ll see it instantly: crossed arms, blank face, refusal to engage.

But here’s the good news:

Respect and relational safety reopen the learning pathways quickly.

So, what can we do as supporting adults, whether we are parents, educators, coaches, mentors…

It’s all about belonging…

Why Belonging Interventions Work So Beautifully

Walton & Yeager’s social-belonging studies demonstrate something powerful:

When adolescents learn that struggling is normal and belonging is earned over time, their whole stress system reorganises.

And when those messages come from older peers?

Even better.

That’s why I’m such an advocate for peer to peer mentorship programmes.

When older boys say:

“I struggled too.”

“I messed up and came back from it.”

“You will find your place.”

Younger boys believe it (this works for all adolescents not just boys).

Mentorship Changes Behaviour

Yeager’s mentor mindset — high standards paired with high support — transforms how boys interpret correction and authority.

It says:

“I expect a lot because you’re capable.”

“I’m holding you to a high standard and I’m helping you reach it.”

“I won’t shame you — but I also won’t lower the bar.”

This is not indulgence.

It is relational discipline.

I wonder if we can reframe our thinking about behaviour then?

Boys Don’t Test Rules. They Test Relationships.

Every rugby tackle, every boundary test, every grunted “okay” is a boy asking:

“Am I safe with you?”

“Do you see me for who I am?”

“Will you hold the line with fairness?”

When adults understand the science of:

social status

fairness

belonging

prediction error

the stress response

and the need for dignity

everything shifts.

I don’t get parenting right all the time.

In fact, I make a lot of errors.

I lose patience.

I misread situations.

I react too quickly.

I forget that their nervous systems are still under construction while mine is, well, not…

But seeing behaviour through a different lens — through the neurobiology of adolescence — has changed everything for me.

It has helped me pause.

It has helped me regulate before I respond.

It has helped me see my boys not as “being difficult,” but as experiencing difficulty.

It has helped me hold boundaries in ways that don’t compromise dignity.

And it has helped me see their signals as invitations, not defiance.

I may not have a particularly enthusiastic audience for my insights at home — the tumbleweed still rolls through the kitchen when I say, “Did you know what the amygdala does?”

But I know, quietly, they’re absorbing little fragments here and there.

And here’s what I truly believe:

There is so much to be gained from understanding the neurobiology of adolescence.

So much behaviour that suddenly makes sense.

So much unnecessary conflict that can be prevented.

So much relationship that can be restored.

And I can’t help but wonder…

If schools embraced this lens fully

if we saw behaviour as communication, not defiance

if we prioritised connection before correction

could we reduce sanctions altogether?

Maybe not every sanction, but certainly the unnecessary ones: the misunderstandings, the escalations, the shame-driven spirals.

Because when adults understand what the adolescent brain is actually trying to do - to protect, to predict, to belong - we stop fighting biology and start working with it.

And that, more than anything, changes everything.

My cheeky chaps…